Product Description

This is a socketed iron javelin spearhead meant to be thrown from the back of a cavalry horse by a mounted soldier. Its small head and heavy construction meant it was designed with armor-piercing in mind. It was used by the Roman Byzantine military and is a superb example that is in rare, complete condition. Roman Byzantine cavalry employed a variety of spears and javelins, some thrown and some used for repeated stabbing of enemy soldiers. The thickness of the socket indicated the heft of the pole they were mounted on. Large poles with small heads were ideal for repeated use where the pole would not break and the head would not get stuck in an enemy's body. Spearheads for use with smaller diameter poles and shafts were designed for throwing where as the weight for power in the throw, and the narrower shaft aided, flight. Professionally cleaned and conserved in our museum lab facility to ensure against further deterioration. INTACT AND COMPLETE WITH NO REPAIR OR RESTORATION.

At this time in Roman history, the cavalry was the primary strength of the Roman military! The cavalry was the most powerful and important weapon of the Byzantine Roman army as opposed to the ground forces of the earlier Roman Empire. Protection and support of the cavalry was vital to victory. Loss of the cavalry was a sure defeat as the ground troops of the Byzantine Roman army by this era, were ill-equipped and inferior to the invader armies.

This item was used by the Byzantine Roman armies defending the Empire's northern border along the Danube River in the present day East Balkans. This region was the northern-most boundary of the Roman Empire for most of its duration and evolution into Byzantium right up until 1336 AD when the area fell under Ottoman rule. In the Balkans, Roman camps and fortresses along the Danube were constantly being challenged by opposing tribes and armies. The river served as a natural barrier against attacks from the north. Collected from a region that was once occupied by the Byzantine Roman military as they fought against the challengers of the Christian Roman Empire, they were utilized by Roman soldiers in one of the many violent and frequent battles that took place in defense of Byzantium.

Unlike most metal artifacts sold on the market that are untreated and uncleaned, our specimens our properly cleaned, inspected and conserved in our museum conservation lab prior to being offered for sale to our clients. Every piece we offer is cleaned, stabilized and treated in our facility. If it were not treated properly, it likely would deteriorate into further corrosion and possibly disintegrate into pieces. All our artifacts are guaranteed for life to not further corrode in normal storage environments. The vast majority of sellers of metal artifacts do NOT PROPERLY clean and treat their specimens and many do nothing at all. If those artifacts are NOT treated and stabilized correctly, THEY WILL CONTINUE TO DISINTEGRATE AND CORRODE AND COULD EVENTUALLY FALL APART INTO PIECES.

The Roman sagittarii or archers were either formed out of auxiliary units or were trained members of the Legion. Many Roman units of bowmen were originally recruited in the Middle East and in the Danubian provinces. Trajan's column shows these troops using distinctive native clothing and equipment including conical helmets, chain mail, long tunics and powerful composite bows fashioned of laminate wood and horn.

A diverse variety of arrowheads were employed. Heavy tri-lobed projectile points were designed to penetrate armor with leaf-shaped points effective on "soft targets". Throughout the Near East arrows were normally secured to their shafts with a tang rather than a socket as in western Europe. In the "single use" situation of warfare, this method was just as effective and required less construction time and materials. Arrow shafts were usually constructed out of wood but cane was sometimes employed. Each archer carried an average of 30-40 arrows in their quiver. In addition to full sized arrows, Roman archers would also fire small arrows or darts down a channel called a solinarion. Such darts have about double the range of a full-sized arrow and are harder to see. They were used as harassing fire against approaching formations. While a dart would rarely cause fatal injury, striking a man or horse in the face or eye would be a serious discouragement and help to break up a formation. Archers were sometimes employed as skirmishers or deployed behind lines of heavy infantry to provide covering fire. The simultaneous storm of thousands of arrows raining down upon enemy troops must have been a nightmarish site! The opening battle scene of the film 'Gladiator' reenacts to exactness the visual horror and deadly effect the Roman archers had against enemies of the Empire!

Perhaps no other epoch in history is so unique, extensive and yet, as much forgotten as that of the Byzantine Roman Empire. From the founding of its new capitol in Constantinople, 330 AD to its final fall to the Ottoman invaders in 1453, over eleven hundred years of history has virtually been lost in most minds of the Western world. Ironically, it is this exact history that has extensively shaped the Western cultures today, especially those of the Christian faith.

Perhaps no other epoch in history is so unique, extensive and yet, as much forgotten as that of the Byzantine Roman Empire. From the founding of its new capitol in Constantinople, 330 AD to its final fall to the Ottoman invaders in 1453, over eleven hundred years of history has virtually been lost in most minds of the Western world. Ironically, it is this exact history that has extensively shaped the Western cultures today, especially those of the Christian faith.

No event in Western history was probably more pivotal than that of the Christian conversion of the Roman emperor Constantine I. Up to that time, Christians were heavily persecuted by many of the previous emperors and the religion was outlawed. That would all change in 324 AD with a miraculous military victory and subsequent conversion to Christianity by Constantine I at the Milvian Bridge. From this point on, Christianity became the official religion of the Empire. A new capitol was established in Constantinople (present day Istanbul, Turkey) and power was fully transferred from Rome to Constantinople in 476 AD. It was not the end of the Roman Empire but a continuation and fascinating transformation of Roman rule that would last for another one thousand years!

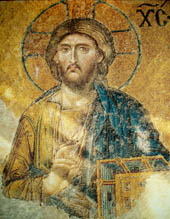

In the Byzantine Period, the Roman Empire and Christianity were completely interwoven. It was the quintessential example of the UNION of church and state. What was once the ancient world's greatest enemy of the faith, overnight became its most devoted advocate. The classic architecture, style of dress, and overall appearance of all that was "Old Rome" took on a new and intricate style that the world has never seen before or since. This was not only attributed to the influence of the capitol's new geographic location, but also to the foremost prominence of Christianity in the Roman world.

In the Byzantine Period, the Roman Empire and Christianity were completely interwoven. It was the quintessential example of the UNION of church and state. What was once the ancient world's greatest enemy of the faith, overnight became its most devoted advocate. The classic architecture, style of dress, and overall appearance of all that was "Old Rome" took on a new and intricate style that the world has never seen before or since. This was not only attributed to the influence of the capitol's new geographic location, but also to the foremost prominence of Christianity in the Roman world.

A well-known remnant of the Byzantine Period is the stunning and unique art of the religious Icons. This abstract spiritual style can be immediately recognized and is evident in not only paintings and mosaics but also the era's architecture and coins. What was once thought of as crude numismatic issues are now appreciated as highly stylized symbols of the Romans' devout faith.

After the establishment of Constantinople as the new capitol and navel of the Roman world, the Empire continued for almost a millennium eventually bridging ancient and medieval history but not without its share of enemies. Numerous challenges of foreign armies took its toll on defenses and finally, on May 29, 1453 AD, the Muslim Ottomans overran the crumbling city walls and the sun set forever on the greatest empire that the ancient world had ever known.

US DOLLAR

US DOLLAR

EURO

EURO

AUSTRALIAN DOLLAR

AUSTRALIAN DOLLAR

CANADIAN DOLLAR

CANADIAN DOLLAR

POUND STERLING

POUND STERLING